Sidi Kassner

Sibirische

Erinnerungen.

Von

Czernowitz nach Sibirien deportiert

und ein neues Leben in Israel

1941-1967.

Chapter

1

Travel

Baggage

June 13th

1941, is a day I especially remember…It was the day that the massive

deportation of Jews had begun from Czernowitz to Siberia. From the

beginning of the Russian occupation of Czernowitz I was living with my

husband at my in laws…

On the night of June 13th, we were awakened by Russian soldiers who

gave us half an hour to pack our bags and leave the apartment. My first

thought was that we would probably walk a lot so I didn't even bother

going to the closet were our new wardrobe hung, from our wedding last

year. Instead I went to a box full of winter clothes; I took out an old

winter coat that I used to wear during my school years, some sweaters

and other warm things. I stuffed everything into two suitcases. I then

went into the bedroom, and I rolled a pillow into a blanket and tied it

with a cord to make one package. Now my family and I were ready to

leave our home forever.

In the darkness in front of the house, stood a truck, in which there

were already people who were in the same situation like us. We had no

choice but to get in the truck just like them.

On the road, we continued to pick up more people, until the truck was

fully loaded. When we reached the railway station and got out, my

father-in-law and my husband took our two suitcases, and I took the

pillow and we all approached the train, which consisted of many cattle

cars. Here my husband and his father were ordered to enter into a

cattle car, and my mother-in-law and I were ordered into another cattle

car. Both suitcases stayed with the men and my mother-in-law and I were

left with just the pillow and the blanket.

Once in the cattle car my mother-in-law and I started looking for a

place to sit on the floor and we found a place to sit between two

families, and we tried to get used to our new "home."

The train didn't move from the station for three whole days; there were

always new people arriving and being added into the car until our car

was so packed it was overflowing.

On the third day, the men's car was detached from the train and moved

to another track, so that it was standing in parallel of our car. I

suddenly heard my name being called and when I came to the little

window, I saw my husband in the window of the train on the opposite

side. He quickly grabbed some of our stuff from the suitcases; bundled

it into a towel and threw it out the window and asked a passing woman

to hand the bundle to me through my window. He then yelled to me a few

words while his train began to move. That would be our farewell for ten

years…

My train drove me and my-mother-in-law into an unknown future. We took

the long trip, even without the most necessary baggage.

First

Encounters

After a month

and a half of inhumane travel by train (over the Ural) by ship and by

boat we arrived in the village in the Taiga of Siberia, Scherstobitowo,

which was many 100s of kilometers away from a railway station.

The first person

we met when we arrived at the village was the miller, who worked at the

water mill. He was like a figure out of a novel by Tolstoy; a long

black beard, black boots, dressed in typical Russian style shirt and

trousers made out of coarse cloths.

The peasants of

the village lived in huts made out of wood from the fallen trees around

the village. We were led to a hut, where a sulky woman quite young but

with a much older appearance expected us. The hut consisted of one

room, in the middle of the room stood a brick-clay stove. On which the

meals were prepared in heavy iron pots on an open fire. One could sleep

on the "upper wall " of the stove, which was also the preferred place

of the landlady.

My mother-in-law

and I were allocated a corner of the room, where a wooden bed stood on

which rested a straw filled mattress. We put our meager belongings

under the bed.

In the evening,

the three sons of our landlady came home from the Kolhoz, who were the

ages of 17, 19, and 21. All three spooned their evening meal out of a

large bowl and laid on the floor for their night's sleep. This was how

we spent our first night at our new "home."

In the morning,

after the young men left for work. We wanted to wash ourselves.

However, the landlady explained to us that the "Bania" a sort of steam

bath, that was located in a small hut in the yard, was heated only once

a week on Saturday for the whole family.

We were then

summoned to the office of the kolhoz; and all heads of the families was

invited to submit an application in the name of all family members for

admittance into the kolhoz. This application was in order to obtain

work and bread rations. In view of the fact that our family only

consisted of me and my mother-in-law, I had to submit the application

which then enchained me to the kolhoz for the 15 years.

First

Victims

In October the

Siberian winter began earnestly; the first snow blanket reached the

height of more than a meter. The temperature was around minus 30-40

degrees C. It was so bitterly cold that when we brought water from the

well to the hut, on the way the water froze in the pail. It had to be

defrosted inside the hut.

The situation of

us deportees became more fatal every day; we had neither proper winter

clothing to withstand the frost, nor food to sustain us. The younger

people had to go to work in the Kolhoz in order to obtain the necessary

bread rations. We put every piece of clothing that we still possessed

on us, and swaddled our feet in sacks, in order to avoid that our

shoes' sole should not freeze with ice. We filled heavy sacks with

grain and stocked them inside the grain warehouses. We cleaned the

stables, where everything was frozen stiff. Due to the heavy work and

the frost the skin of one of my fingers burst and became infected. It

caused me a lot of suffering for a long time. It was indeed very lucky

that it did not result in blood poisoning.

The older

deportees, who were not canvassed to work in the kolhotz were unable to

withstand the hunger and bitter cold. We saw everyday how frozen

corpses were taken in sleds outside the village. A great fire was

burning in order to thaw the frozen earth so that the corpses could be

buried.

The winter

1941-42 was the cruelest one for us deportees. Each family lost most of

its relatives. The terrible conditions caused more and more deaths.

As the war raged

in Europe in Russia at the time, we were completely isolated from the

world. Nobody knew where we were. We also missed any news from our men.

There was noway anyone could help us, and we were left to our destiny.

Chapter 2

The Turning Point

Due to the fact that I was so young at the time, and was sharing every

bit of food with my mother –in-law, we were both able to survive the

terrible winter of 1941-42.

In the spring of 1942 all the men of the kolhoz were mobilized and sent

to the front. Among them was also the book keeper of the kolhoz. The

women, old people, children, and deportees were the only ones left;

they had to do all the work of the kolhoz.

During the year of Russian occupation in Czernowitz I learned the

Russian language verbally and in writing, and I worked as a book

keeper. Therefore, I was asked to keep the accounts of the kolhoz after

permission was granted by the authority.

This was the big turning point which would influence our destiny in the

future. I was not obligated anymore to perform the heavy physical work

outside in all weather, I now worked in a closed room and the lack of

warm clothes was not so terrible anymore.

Among my work I had to oversee the production of the milk farm,

delivery of grain to the state, stocks in storage, accounts' with the

banks and other organizations. I also had to calculate the labor days

and the distribution of goods to the kolhoz members.

After each quarter in the end of the year I had to present a balance

sheet. During the long winter months I travelled once a month together

with the kolhoz members by sled and horse to the regional center

Pudino, were I took part in meetings. During these conferences I met

other kolhoz book keepers some of them were also deportees.

A few families from Czernowitz lived in Pudino among them was also a

family that were friends of my husband, and they welcomed me with great

joy. Whenever I came to Pudion, and in spite of the fact that they were

a family of five in one room, they improvised and arranged sleeping

arrangements for me on a table. We didn't sleep much during those

winter nights. But rather exchanged reminisces of our past.

First News

After the first victories of the red army at the front, the situation

in the country became more relaxed and the first letters arrived. Among

them were also letters sent by the men in the camps to the relatives in

Czernowitz. They wrote that they were in the camps in the north of

Russia along the river Vorkuta. A majority of men perished in the camps

due to the nearly inhumane conditions there.

At the same time the women and families wrote from the Siberian exile

to the relatives in Czernwotz and informed them of their address. Those

family members heard for the first time about the whereabouts of their

loved ones. A lawyer from Czernowitz who was in exile in the Siberian

Backzar region came up with the idea to compile a list of all the known

addresses and to send them to the families in the various parts

of Siberia.

We received at the end of the year 1944 after 3 years, the first letter

from my husband. He wrote that he was sentenced to five years

banishment to a concentration camp and that his sixty year old father

was unable to withstand the terrible exertions and perished on the way

to the camp.

The conditions in the camps; were atrociously difficult, everyday one

had to march for many miles to the woods to cut down trees and stack

them; all this in deep snow and in the bitter cold.

In the evening one had to return by foot with their wet clothes to the

barracks and to sleep on bare wood. The nourishment consisted of a

small ration of bread, which was roped in many instances with threats

with the use of a knife. My husband was due to be released in 1946 … if

he was able to survive until then.

It was indeed a miracle that he survived so far, probably due to his

young age.

Disappointed Hopes

On 9th of May 1945 the Second World War ended, and millions of

survivors hoped to be free, and finally to return to their

long-lost homeland. We were among the hopeful!

Unfortunately, our hopes remained unheard and the nearby peace brought

no improvement to our predicament. My husband still had until 1946 to

meet his punishment in the camp and, only four years had passed out of

the 25 years that my mother and I were to be enforced to stay in

Siberia The supervision of the commander was just as strict as before,

and we could not change our stay in Siberia and our compulsive

membership in the collective farm.

In the few letters we were able to share with my husband, we were

considering carefully our future plans. My husband insisted after his

release to join us in Siberia. For my part, with the experience of life

in Siberia, I was against it. I only hoped that my husband would return

to Czernowitz, so that he would somehow help to reunite us. What turned

out later to be a great disappointment.

With the end of the war, the first returning soldiers began to return

to Siberia to the collective farm. They were mostly wounded and

crippled, what was an additional economic burden, to the collective

farm. These soldiers for the first time in their lives had come

in contact with the western world and therefore felt more understanding

towards the deportees.

At this time, the first care packages began to arrive from America. In

order to obtain a package, you needed a family member or a friend in a

foreign country, who requested these packages to be sent. The packages

were filled with food - mostly canned food and Nescafe. This would be a

wonderful exchange for potatoes.Otherwise, nothing changed in our

monotonous life. The kolkhoz continued its strict laws.

Chapter 3

The

Return

In midst 1946

the day finally arrived. My husband, who managed to survive his camp

sentence, was liberated. However, the return journey to Czernowitz was

not much easier than the journey to Komi ASSR.

At first he had

to travel by truck trailers; that transported tree trunks from Komi

near the North Pole to a province in Russia for timber. Only after

reaching the European part of Russia, was he able to slowly make his

way, during many weeks by train, to Czernowitz.

Here an

additional disappointment awaited him. His discharge document

stipulated that he was an "untrustworthy individual" and as such he was

refused a residence permit in Czernowitz. He therefore was obligated to

travel to Kotzman, a small town not far from Czernowitz, where he found

shelter for a few months at a home of a friend; a physician and his

wife.

After he finally

managed to obtain a residence permit for Cernowitz, he travelled only

to find that all his relatives and friends were gone. They were either

perished in Transnistria or the few who had survived took advantage of

the repatriation law and immigrated to Romania. He was thus obliged to

build a new life in Czernowitz. He found work as a book keeper at a

dress-making cooperative; he rented a furnished room, and submitted

applications for the reunion with his family and their return from

Siberia.

Unfortunately,

he received no replies and later on only negative replies. However, he

managed at the time to make contact with my parents in Constanza in

Romania and to send them my address in Siberia.

Several months

elapsed before I received in my hand my first letter from my parents

and my sister…after not hearing from them for 6 interminable long

years. They had suffered much grief and anguish due to our long

unwilled separation, and now hoped for a reunion; which took place only

after another 21 years.

The

Failed Escape

Yet another year

passed and our many requests were denied to have our family reunited.

We assumed that our request was obliterated because I was still capable

of working and therefore there was no reason to release me. My

mother-in-law, an elderly woman, who could have been released, was also

denied because of her connection to me. Therefore, we decided that I

should leave Siberia illegally. The only way to do that was for me to

join a convoy of Kolchoz-sleds who would drive over a 60 km-long frozen

swamp, in the winter, to deliver their products to the state to a

nearby town.

As described

previously, I failed to escape twice; and I received a prison sentence.

Due to the fact that there was no substitute for my working position in

the kolchoz, the management of the kolchoz decided to request an early

release. And so I went back to my old position.

Meanwhile I had

received from my parents, from Romania, two large packages with warm

clothing. Finally, we could replace our worn clothes that were made of

burlap and old blankets to normal clothes. Although, we sold the best

pieces in the packages for a considerable sum with this we bought

ourselves a little hut.

So we finally

solved the problem, after many years, of having a "landlady". More

importantly was the fact that near the hut was a small garden where we

could grow our own potatoes and other vegetables. However, we did not

have any seeds for cultivation. A friendly deported family was kind

enough to agree to cut the tops of potatoes which had sprouts; and to

donate them to us for seeding. We planted the seeds in the early spring

and then collected for the first time in the fall; a very modest potato

harvest.

Exile

and Reunion

At the end of

the 2nd World War, the Soviet Union once again occupied Czernowitz,

northern Bukovina, and Bessarabia. During the peace negotiations in

Yalta and later in Paris these territories were officially rewarded to

the Soviet Union

During their

occupation the Soviets had decided to change the local population with

Soviet citizens. They wanted to remove the "untrustworthy individuals"

from the areas surrounding the borders- including of course those

individuals who were freed and returned home from the camps.

And so in 1949

my husband was arrested again, and was taken from Czernowitz prison to

a prison in Lemberg (Lvov), and then to a prison in Urals. From the

Urals, he was then exiled to Siberia. He was sent into the region of

Kemerovo, south of the Trans-Siberian railway line, while my mother and

I lived in the Tomsk region - north of the Trans-Siberian railway line.

Once he arrived,

he had to work hard in the fields and to do other auxiliary works to

survive. At the same time he began again with writing applications to

join his family. Only two years later in 1951, his wish was granted. On

November 1st, 1951 he was finally able to come to us in Scherstobitovo.

After being

separated for more than 10 years, the reunion with his mother and I was

indescribable. We fell weeping into his arms, looked at each other and

discovered traces of the heavy years of deprivation and hard work that

we had been through.

We had been a

young couple when we were separated - the hard struggle for survival

had made us mature, and yet we were grateful to have found each other.

We could not

stop telling each other again and again what we had gone through during

our separation; we also mourned together the many close people,

including his father, who we had lost.

We were finally

happy to get rid of the uncertainty of possibly not ever meeting each

other again which had plagued us for years. Although, the location of

our reunion in Siberia did not meet our dreams and desires; at least we

were able to be incredibly happy, to finally have the opportunity to be

together and to share a destiny in our future.

Chapter 4

New

Difficulties

A week after the

arrival of my husband in Sherstobitowo, the October

Revolution was celebrated at the Kolhoz, like everywhere else in the

Soviet Union.

My husband was

also invited and was treated with a great amount of

home-brewed schnapps (alcohol-samogon). The members of the kolhoz, thus

hoped to recruit a new member. This resulted in a new struggle for us

because I was determined to prevent that my husband would do the same

mistake I did many years ago, which was to become a kolhoz member.

In the tiny

place where we lived, there was a little chance to find a

monthly paying job. Nevertheless, my husband succeeded in obtaining a

position as a book keeper in the only school, and we were very happy

about this. Unfortunately, we did not take account that the kolhoz

management would voice the opposition to the commander, due to the fact

that my husband got a position in spite of not being a kolhoz member.

The commander then ordered that he be dismissed immediately.

The same thing

happened to him also at the cooperative. Thus a steady

job with steady income was denied to us. The reason was that they

wanted to force my husband to join the kohoz as a member. However we

remained steadfast in our refusal. My husband helped from time to time

in the gardens of the kolhoz members and was rewarded with some

potatoes and vegetables.

In order to be

able to feed our now growing family, we purchased with

great sacrifice a "quarter" of a cow. Yes, this quite common in those

times in Siberia. One cow with four owners, we took turns in feeding

and milking the cow once every four days. The law of nature is that if

you feed a cow one day she will produce more milk the next day. The

result was that the poor cow was undernourished as everyone was

concerned that the next owner would get more milk then the previous

owner. Thus the poor creature gave only little milk to each owner-

which needed to be sufficient for four days, this was impossible. Yet,

a little milk was better than no milk at all.

Death

of my mother in law

An additional

worry, the most terrible of all, befell us. My beloved

mother-in-law fell terribly ill. We went to the hospital in Pudino; and

the physician's diagnosis was cancer of the salivary gland. Of course,

medical assistance was out of the question under the circumstances.

After our return

to Scherstobitowo, few months later my mother in law

was unable to swallow. She died on January 31st 1953 at the age of 65,

literally of hunger. For many years we had fought steadfastly to avoid

such a faith.

Together with

us, there were many peasants who came to mourn my

mother-in-law's death. These were the same peasants who had lived in

the villages around Czernowitz, from which my mother-in-law in the past

had hired her servants. They knew my mother-in-law and were very fond

of her. When they heard of her death they came and built single

handedly a coffin. They also dug the grave in the deeply frozen earth,

not any easy task at all.

Since there were

no more elderly Jews still alive; and nobody was in

possession of a prayer book. One of the deportees, an elderly woman,

wrote down from memory the Kaddish prayer, in Latin letters; which my

husband read at the funeral. Apart from him only I was present at the

funeral, because on this day the temperature fell to -40 degrees C.

The death of my

mother-in-law brought upon the loss of my faithful

companion. For ten years we shared everything, our bed…our nourishment.

She was the person with whom I spent together the most terrible years

of my life. We encouraged and comforted each other and we were the only

family we had. However, we never lost hope to be reunited one day with

our loved ones, this gave us the strength to overcome the horrible

difficulties and to never give up.

Unfortunately,

my mother-in-law was only able to enjoy the company of

her son, my husband, for a single year; before she was thorn from our

midst. She left us a deep void.

Hope

for Changes

Finally a chance

for a change in our lives arrived. In one of my

visits to the Regional center Pudino; a young man, who was

deported

with his parents from Bessarabia and worked in a Kolhoz near Pudino

,told me that he had managed to complete a course a- far through

the

University of Tomsk. He had received an invitation to continue his

studies in Tomsk. The only obstacle was, of course, that the Kolhoz

management would not let him go because there wasn't a replacement for

him. Immediately I declared myself ready to take his place.

We went together

to his Kolhoz's management, who knew me from the

meetings in Pudino, and they agreed to represent my case to the

superior authorities. They would allow me to move from the Kolhoz in

Scherstobitowo to the Kolhoz in Pudino, obviously, without canceling my

Kolhoz membership. However, my Kolhoz did not permit me to leave to

Pudino. Nonetheless I returned to Scherstobitowo and was determined to

do everything possible to not let this opportunity pass, I would go to

Pudino no matter what.

I chose to leave

to Pudino in the beginning of spring, when the marshes

were thawing and the roads still couldn't be used by vehicles. I

pretended to suddenly suffer from an unbearable toothache, and went

alone on foot to seek the way to a dentist in Pudino. On the way there

I encountered several small wooden bridges that allowed passage over

the waters of the thawed swamps; at the time, I did not know that the

Kolhoz dismantled the boards of the cross-bridges, in the spring, to

keep them from flooding. Therefore when I had to pass such a bridge,

there was only one possibility to pass... to crawl on the wooden beams

that remained.

I knew that when

crossing the beams that there was a

possibility that I could lose my balance and fall into the ice-cold

water. Yet, I was desperate; so after a long thought I summoned up all

my courage, sat down on a beam and slid carefully with the help of my

hands over the rushing water to the other side. When I arrived to the

other side, safely, I could not believe that this seemingly

insurmountable obstacle was behind me! I repeated this process twice

more before arriving to Pudino.

Once arriving in

Pudino I was placed in a Kolhoz hut, where a large

family also lived; I slept with the children on the wooden floor.

During the 2-3 summer months I was there, there was no postal service

and no telephones calls and so I stayed completely cut off from my

husband and the Kolhoz.

Chapter

5

Pudino

The regional center Pudino was a large village with small wooden houses

and boardwalk. Next to each house there was a small garden. Pudino

boasted a hospital, pharmacy, bank, school, military commandment, and

many state institutions. There was also a store with groceries were one

could buy only what was available at that given moment. There was also

a black market where one could buy various goods at inflated prices, of

course. The Kolhoz was at a distance of only 2km.

I plunged into my new job and worked between 12-14 hours a day; in

order to become familiar with my new circumstances, and so that my

superiors would be satisfied with my work.

The summer had passed and the marshes of the taiga turned icy, which

enabled the sledges to travel. My husband was thus able to come to me

in Pudino from Sherstobitowo. We began to live together in the same

room with a large peasant family with many children. We slept on the

floor.

My husband immediately began to look for work, and he found a position

as a book keeper in a collection place for furs and skins; which had to

be delivered by the Kolhoz to the state, and was later sent to the

tanneries. Finally he had a monthly salary, albeit a small one. After

the death of Stalin, there was a general sigh of relief which one could

feel everywhere. However we were not allowed to leave the Kolhoz or

Pudino.

Already in 1950s my parents and sister emigrated from Romania to

Israel. After a long period of readjustment my father was able to find

a job in a bank in Tiberius, were my family had settled. My father

deployed a lot of activity in order to get us out of Siberia. He went

to Jerusalem, and met the then ambassador of Moscow, Golda Meir, and

asked for her assistance. My father sent us every year an entry permit

to Israel and every year it was refused by the Soviet authorities.

Nevertheless after 12 years of Sherstobitowo… Pudino appeared as a

beginning to a return to life

Another Step Forward

In 1956, Khrushchev came to power, and with it came a great upheaval.

We, too, deportees could perceive the change. We even got permission to

relocate to Tomsk, the district capital. This permission did not apply

to Kolhoz members like me. My husband, however, was independent from

the Kolhoz; which is what we had fought for such a long time.

Therefore, he began to immediately take the first steps towards

resettlement to the city, Tomsk. He quit his job and went alone to

Tomsk. There he lived with a friendly family, who were together with us

in Scherstobitowo; they had arrived first to Tomsk. He also found work

immediately as a book keeper in The Tomsk City Theatre and won, the

very important, residence permit.

I then wrote an application, to the kolkhoz in which I asked them to

release me from the membership of the kolkhoz, so that I would be able

to join my husband in Tomsk.

At a specially convened general assembly of the kolhoz, I asked for my

freedom. Luckily, at the assembly I had the sympathies of most of the

kolholz members, who had understood that after 15 years of devoted work

in the kolhoz I deserved to be set free so that I could join my

husband. I finally received the long-awaited liberation document that

stated that I was able to leave the kolhoz lawfully.

When I finally had the liberation document in my hands, I could not

believe that these 15 years of my life were finally behind me – The

years of hard work and responsibility that could have at any moment

resulted in a punishment of being jailed.

I had to wait again for the harsh winters to pass and eventually I

flew, in the spring, with a small Yak plane to Tomsk. This aircraft was

at that time the only means of reaching the most remote areas of

Siberia. The aircraft had only 4 seats and while flying I felt it

rattle from the very strong wind that I began to fear that I would

never reach my final destination. Yet I arrived, and I started my life

with my husband, in Tomsk, this time would be the third time of

rebuilding and beginning another Siberian life.

Tomsk

Tomsk was one of the largest Siberian cities, and was an industrial

center. It had many factories, garages and shops, schools and also a

university with several faculties. The houses there were large and

built partly of wood and partly from brick and they had one, two or

even three stories.

Many deportees from different regions of the taiga began to arrive to

the city, after finally being given permission to move to Tomsk. These

were the same deportees who were originally from many countries such as

the Baltics, Poland, Romania, Ukraine and even the Turks from the

Caucasus. And now they had turned into 3 generations: older survivors

who were only a few, the second generation, ours, who was in their late

30s, and the third generation, which was a result of marriages during

the long years in Siberia.

The arrival of the many deportees also brought about reunions with

people who we hadn't seen for a long time. Mostly we met my husband's

colleagues from school and university, as well as many people who we

knew from Czernowitz. We reunited with many old acquaintances, and we

were finally not alone anymore! Yet our closest friendships were with

the deportees with whom we had shared so many years with, in

Scherstobitowo and Pudino.

Most of the newcomers found work in the city of Tomsk. The

intellectuals taught German and music in schools. I, after a short

time, found work as an accountant in a sport institution that prepared

young people for their military service. The staff there consisted

mostly of retired officers and the only 3 women who worked were in my

department, bookkeeping. The salary was quite low, but still better

than then the pay in the collective farm!

After some time my husband was assigned a small room in a house for

theater actors, and we at last had our "own" roof over our heads. We

thought that we had found the solution to all our problems. However, we

were still under strict state control. We were allowed to leave Tomsk

only for brief trip, and those who tried to leave Tomsk, illegally, to

get to Czernowitz were tracked down and brought back to Tomsk.

Apparently, we hadn't completed our atonement yet!

Chapter 6

Rehabilitation

While living in Tomsk we did our best to find better paying jobs. My

husband found a position as an accountant in the municipality industry,

and later he even became a senior accountant at a market.

At that time, in Tomsk, the "Institute of Radio Electronics and

Electronic Technology" was established. They were searching for people

of various professions for their departments. I offered my services and

was accepted as an accountant with a good salary.

One day, my husband got a kidney infection and had to go to the

hospital for several weeks. In the hospital, he decided to write the

Attorney General's Office in Moscow. In his letter, he described the

many hard years of punishment for his family and asked for our pardon.

Surprisingly, after a few months we received - a positive response to

his letter, we had been pardoned and liberated. Of course, just like in

1941 when we were first deported, we didn't receive any explanation as

to why we were being liberated. This happened in 1956, when Nikita

Khrushchev was in power and he fought against Stalinism and was trying

to improve the reputation of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Due to our pardon, our life improved; we no longer had to register with

the headquarters. Finally we could leave Tomsk, and the way home,

Czernowitz, was technically free. But in practice there were still many

obstacles in our path, which had to be eliminated. For example, in

order to obtain a residence permit in Czernowitz, one had to have a

stable job and an apartment. This proved to be very difficult, since

there was a large population of migrates from Soviet Russia and Ukraine

to Czernowitz. Many apartments, which were abandoned by the Jews who

left to Romania, were immediately occupied by party members or

high-ranking Soviet officers.

How could we give up everything in Tomsk so lightly without knowing

confidently that we would receive a residence permit and a secure roof

over our heads in Cernowitz?

Trial to Return

In 1962 my husband had a month off and we decided that he should go to

Czernowitz, in order to seek work and an apartment. He drove with a

friend to Czernowitz, whose family also lived in Tomsk. The journey by

train took three days and three nights from Tomsk to Moscow and then

another day and a half from Moscow to Czernowitz. By night they slept

in their seats.

When my husband arrived in Czernowitz, he found a strange city with

Russian-Ukrainian population, and the few Jews, who lived in the city,

were newcomers from the Soviet Union.

The friend, with whom my husband had made the trip from Tomsk with, met

by chance an acquaintance who helped him find a job in Kishinev in

Bessarabia. He later took his family from Tomsk to Kishinev. My husband

on the other hand, his efforts to find work and housing were in vain.

His holiday came to an end and he came back empty-handed to Tomsk.

We continued to live in Tomsk, worked and hoped for a new opportunity

to return home. In May 1965 we celebrated our silver wedding modestly,

which I described in a separate article.

In August 1965 I took two months leave from my job and began to plan,

once again, a way to return to our home in Czernowitz. This time I was

more successful because some friends of ours, from Siberia, already

lived in Czernowitz; I travelled directly to them. They received me

very warmly and I could even live with them for a while, so I could

easily keep trying to find a job and an apartment. After a few weeks,

another Siberian friend helped me to find work in a food company as an

accountant. The company was on the outskirts of Czernowitz, in Sadagura.

I immediately started to work and I wrote my husband that he should

give up everything in Tomsk and come to me in Czernowitz.

Czernowitz, 1965

After I found work in Sadagura/Cernowitz, I rented a furnished room on

the main street. With that all the conditions for a residence permit in

Czernowitz were met; I received a permit without much difficulty. I had

finally returned to my beloved homeland but as I looked around I

realized that the Cernowitz I knew was gone.

The city of Czernowitz had suffered, not much, during the Second World

War. Only the dome of the Great Temple was burned and a few houses in

the street were damaged. I strolled the familiar streets of the city

and I saw the place that my grandparents had lived in and I began to

imagine my grandmother sitting at the window. As I continued walking I

saw my parents' house and I said here there house had

stood, here I had gone to elementary school, here I

attended grammar school –, here, in my dance school I had met my

husband, and over there was the bus stop, to which he had accompanied

me to every evening, and there is, the "Jewish home" where our wedding

ceremony had taken, and here is the house of my in-laws, from which we

had been picked up for deportation. My memories began to come to life

and my thoughts wandered as naturally to the familiar places. Yeah,

sure, everything was still there - but suddenly everything was strange.

I could spend hours walking throughthe familiar streets from childhood,

without seeing anyone I knew.

In the men's lane, on the promenade, where we usually had met many

acquaintances and friends who always had greeted us with hello; now

there were only passing stranger. All the shops were closed and the

grocery store, the only place that still sold goods, there stood lines

and lines of people. I felt that my home had gone through so many

changes over the past 25 years, and to me it seemed foreign. Still, I

wanted to return "home".

I wrote my husband in Tomsk, that he should let my work place know that

I would not be returning, and that he should begin to set his own

affairs in order. He immedialty grabbed the few things we had, put them

in two suitcases and came by plane to Czernowitz. We would now start a

new phase in our life, this time in Cernowitz.

Chapter 7

Organization of our new life

Since we were now rehabilitated, we had the right to reclaim our

apartment in Czernowitz, which was registered under my husband's name

in the city archives. So my husband got himself all the necessary

documents and went to the mayor of Czernowitz, in order to demand the

return of our apartment. It turned out that in our apartment lived an

important Russian judge with his large family. In order for us to

reclaim our apartment it would take a court decision, which could last

many years. The mayor, therefore, proposed to my husband to get us an

apartment in a neighborhood near the airport. This would be a two-room

cooperative apartment, and the rent would be minimal and could be paid

within 25 years. We, of course, immediately agreed. The price of our

apartment was much more expensive because it had three rooms and was in

the center of Czernowitz. The mayor also gave us 3,000 rubles to buy

new furniture for our new home. Once we agreed to the new apartment we

would have to disclaim our old apartment.

After we had established ourselves, I had to quit my job in Sadagura

because it was too far from our new apartment. Only after great

difficulty, I finally found a new job as an accountant, at a children's

day care, in the neighborhood of the university. The only catch: my

salary was now much lower. My husband also found, with great effort, a

job as an accountant in a chemical factory in Czernowitz. So then we

began our new life in Czernowitz.

Meanwhile, we built, slowly, a small circle of friends with families

that had arrived from Tomsk; we did not have to interact with local

population. Also, near us lived relatives of my husband, who did not

leave Czernowitz. He was an electrical mechanic, married and had two

daughters, who were studying in Russia. They often came to visit in the

evening and we developed a close relationship with them, which helped

us to overcome our loneliness.

Permission to Depart

We lived for over a year in Czernowitz, worked and had a good

apartment, the best in the past 25 years. Our life began to be normal.

Like every year, my parents sent us an entry permit into Israel, which

we submitted to the authorities. Unlike the previous twelve years,

during which we received rejections, this time there was a positive

response. We were allowed to depart to Israel! We could not believe our

luck. Finally, all the difficult years were behind us; we could begin a

new life and be united with my family in Israel!

My husband had to go to Moscow to obtain official permission to leave

the Soviet Union. When he returned, we began - as so often before – to

set our affairs in order and to return the apartment to the

cooperative. Again, we had to quite our jobs, for which we had fought

so hard for a year earlier. With the proceeds from the sale of

furniture we bought a refrigerator, a washing machine and a television

set, which we shipped to Israel. We were allowed to take only 200

dollars in cash. We bade farewell to the few friends we had made.

Yet, despite all the hope to finally be free, there was still something

threatening in arriving in the unknown.

On the 23rd of May 1967 it was finally over. We took the train out of

Czernowitz up to the Hungarian border, where we were taken over by

Hungarian customs officials. Then we continued our journey to Budapest.

There we stayed in a hotel for the night, in the morning we continued

by train to Vienna. At the train station in Vienna, "Sochnut" officers

were waiting for us. They took us to a meeting point for new immigrants

to Israel. For the first time we felt our "belonging" to Israel and its

government, and we waited full of hope for a better future.

Arrival in Israel

After an overnight stay in Vienna, the next morning we wanted to visit

the Austrian capital, but we were not allowed to leave the meeting

site. It was the 25th of May 1967. In Israel, they were already

preparing for war; they wanted to send us to Israel as soon as possible.

After all the formalities were done, they took us to Vienna's airport.

From there we boarded, an EL AL-plane, in the late afternoon that had

brought us to Israel.

When we landed in Ben-Gurion Airport in Israel, it was already night

and all the airport lights had already been turned off. The airport and

the surrounding terrain looked very obscures so we could not perceive

our new home. My parent were waiting for us in the airport hall;

finally - after 27 years of separation - we were in each other's arms

and tears of joy and emotion became too much to suppress.

Our first impression was that my parents were already old, but we were

not young anymore either. The many years of separation had left deep

scars in all of us. But ultimately, we were finally together again. The

dreams of the many sleepless nights had finally, finally became a

reality; we were among the few to whom it was granted.

At first we could not talk much with each other since we first had to

answer the many questions of the "Sochnut" officials. These officials

made our first immigration documents. We only left the airport at dawn,

and then we took a taxi to my parent's home in Tiberias.

On this trip we could not help but notice the many orange groves and

lots of trees planted along the road. In our minds, Israel was a

desert, we didn't expect so much green, we felt very enthusiastic. When

we drove through Wadi Ara valley and saw the many Arab villages on the

hills, we were extremely surprised. We would know more later about life

in Israel.

In Tiberias awaited my sister, who I had accompanied to take a train

from Czernowitz to Constansa, with my mother for the last time on Jun

11, 1940 as a 12-year-old girl. My sister now was waiting for us with

her husband, whom I met just now. I had a 39-year old married woman

before me. Her marriage, as well, was childless like ours.

The first days we spent in Tiberias there were many questions and

answers for both sides. We wanted to hear everything that we had missed

due to our long separation. All our relatives were now scattered all

over the world. One of my mother's sisters had stayed with her husband

in Bucharest, the second moved with her husband to Germany, and the

third, whose husband was killed in Transnistria, immigrated with her

daughter and the husband's family to Chile. The brother of my mother

was no longer alive. In Israel, only lived a cousin of my husband with

his wife and son. Otherwise we had no other relatives in Israel.

My sister and her husband showed us the holy land. We went walking in

Tiberias, where there is the beautiful Lake of Galilee and the Golan

Heights in the background. They told us that on the Golan Heights, the

Syrians had bunkers from which they shoot on the Israeli kibbutzim. We

also went to the ruins of Capernaum and Mowil Arzi, who supplied almost

the entire country with water. The first impressions sparked

excitement: Israel had created so much in the short time of its

existence!

We talked a lot about our plans in the new country. But the first

condition was learning the Hebrew language, without whose mastery we

could not live. This is why after the weekend we travelled from

Tiberius to Tel Aviv. There we received from the Suchnot, a reference

to an Ulpan academy, in Haifa, to learn Hebrew.

The Six-Day War

On the morning of the 6th of June 1967, while we were on the way to Tel

Aviv, by bus, from Tiberais we saw many military vehicles with troops.

We couldn't understand why they were there. Of course it was because we

still could not understand the radio messages in Hebrew, and only when

we arrived in Tel Aviv at the Sochnut, we were told that a war between

Israel and its Arab neighbors had begun.

Immediately, at the Sochnut we were given documents that would allow us

to participate in the Ulpan in Haifa, and we were also given room and

board. In addition we were advised at the Sochnut, to make our way to

Haifa, as soon as possible. We took the first train from Tel Aviv to

Haifa and from there a taxi directly to the Ulpan.

At the Ulpan, the director was already expecting us; and he welcomed us

with warm words. He showed us to our room and calmed us down by saying

that we would be completely safe here, although the windows of the

building were sill protected against bombs by paper strips glued

together.

In the Ulpan, there were already many new immigrants from countries all

over the world: Romania, Poland, the Baltic countries, France, the USA

and Argentina. Everyone had started to make their life in Israel, just

as we did, by learning the Hebrew language under the shadow of war.

After six days, Israel was victorious and the war had come to an end.

All of our friends from Haifa and Tel Aviv came to the Ulpan, to visit

us and to wish us luck. All of these friends already lived, several

years in Israel. They were doctors, lawyers, engineers, journalists,

government officials and merchants that had been able to afford nice

homes and expensive cars.

After 27 years, we saw for the first time the results of how much we

had lost in our lives. Yet, we hoped that finally in the free Jewish

country, perhaps we would achieve a better future.

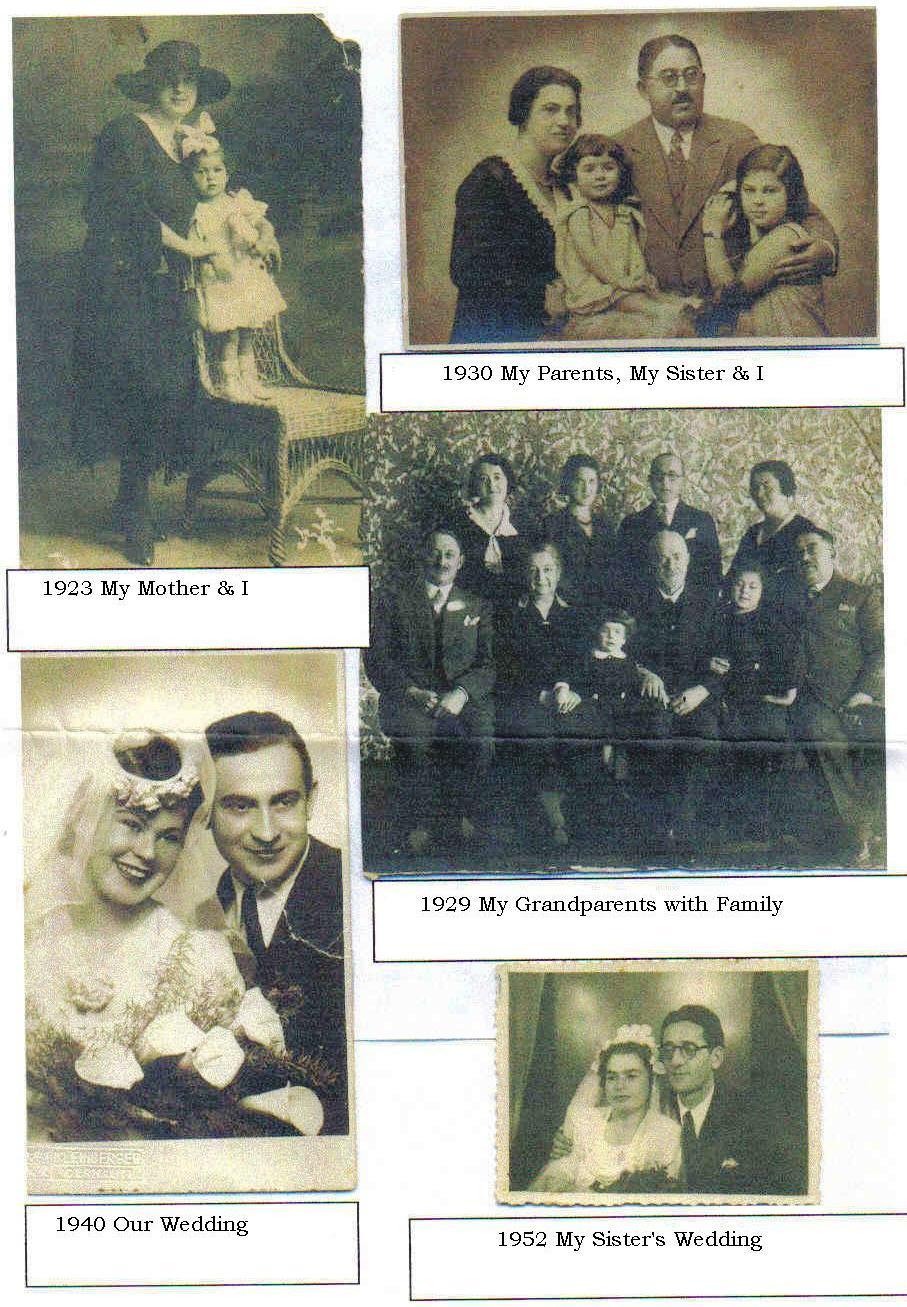

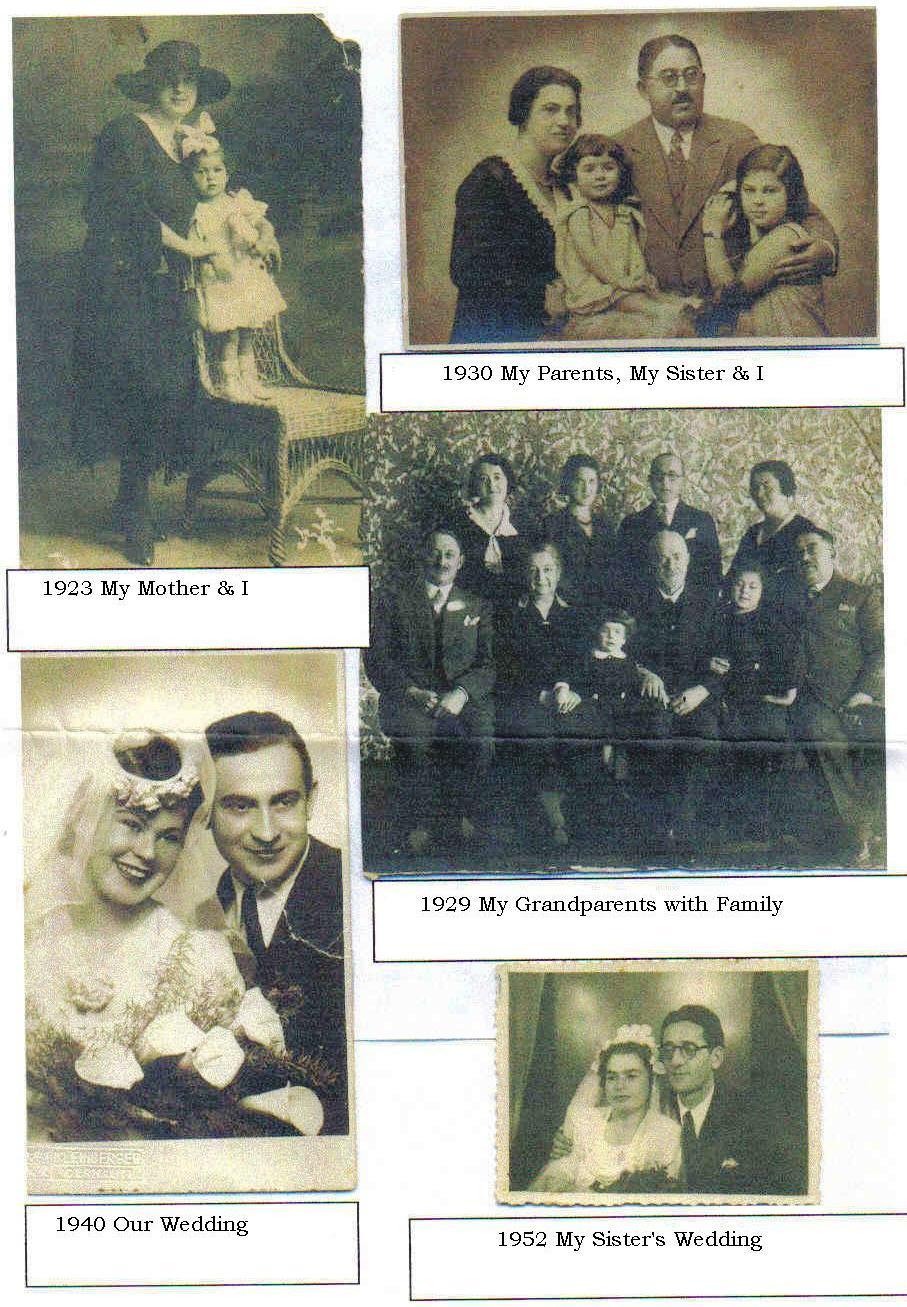

Photographs

--End--